There are many things one thinks about when confined to a hospital bed a relative isolation for long periods of time. Mostly they were around how much I missed food and how much I missed lifting weights.

I have always been a good eater but I’ve never been a great lifter of heavy things. I’ve done ok and wouldn’t shame myself in most gyms, but I wouldn’t call myself “strong”, unless my kids ask and then I’m the Hulk.

My recovery from life threatening and changing illness (acute necrotic pancreatitis with other stuff including an aneurysm, infections and septicaemia) was not a moment of clarity or an epiphany, just a slow return to what I used to do with the resolution to do it better. My experiences have shown me that life is fragile and short.

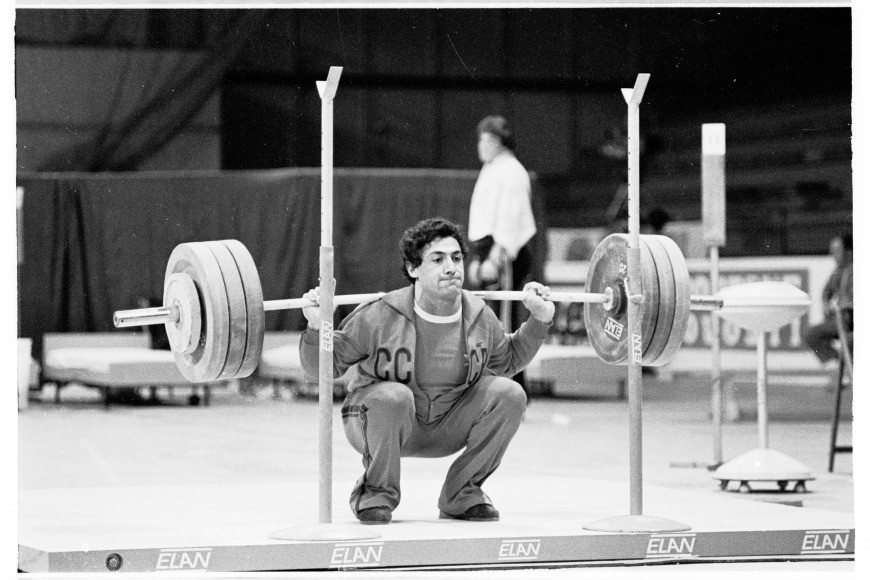

As a young man I had dreams of physique based glory, none of the magazines mentioned performance enhancing drugs and their pivotal role though. I continue to avoid such things as a personal preference rather than any moral or medical reason. I drifted towards infrequent powerlifting as a way to motivate and benchmark my progress, I would recommend it, plus you can eat more.

When I started to lift weights again my insides were still in the process of healing, I was a lot smaller and weaker. There were things I learned from the build up again and things I continue to learn as I progress towards my old strength levels and hopefully beyond.

In thirty years of training my life has got in the way of a million different routines and schedules. I’m still drawn to the lure of a glossy advert and an accomplished lifter whose philosophy seems to resonate with some aspect of what I know, from experience or research, to be broadly true.

One of the factors that I think many authors fail to take into account are the personal circumstances of their subject. Some have tried to make a myriad of adjustments and differing schedules to widen their audience appeal, but the fact remains, I cannot and should not train the same as I did when I was eighteen.

I will not seek to offer broad advice based on my perceived notions of circumstances, age, gender and experience. It will not take a rocket scientist to deduce that a younger man with very little in the way of work or family commitments might be able to push a routine harder than a full time, shift working single mum in her 50’s.

However, as one ages the wily veterans amongst us would have worked out what constitutes good form under a relatively heavy load. They will have worked out the cues to adjust and push and pull at the right times on the lifts. A younger trainee might be blessed with boundless energy, but I’m sure most have seen the car crash methods of training and the frightened cat deadlifts that would leave us Masters lifters in a full body cast if attempted.

When you study a popular routine and critique it, as I have been doing for several years, the basic philosophies seem to ring true. Start relatively light and easy and build up in both weight and volume over time, usually to a peak, rinse and repeat. A lot of work is done with repetitions in the 70-80% range for “working” sets. Practice of the skill of lifting under a heavy load is done for low repetitions less frequently, normally near to a competition or testing period.

In my rehab from both hospital and a million injuries along the journey I can categorically say, without fear, that the squat, bench and deadlift are great exercises when performed well. Learning how to perform an exercise properly is one of the keys for both long term progress and development. I recently saw a clip of a powerlifter set up for a squat, I had never seen him lift before. The first thing that stood out was his great thigh development, it should come as no surprise that this man squatted deep, upright and smoothly. I could name names but you should seek out the top performers in the powerlifts, especially the ones who have been doing well for years or decades and have a look at their form. Far from being “built to lift”, most of these lifters have spent years perfecting their form – I think the people we think as “built” for a certain lift are ones that can quickly find the sweet spots and are able to keep finding them.

In the vast majority of cases the average lifter will be selling themselves short on the amount of effort they can exert in the gym, I am no exception to this. Poor form and exercise selection will prematurely reduce the amount of quality work you can perform. Spending hours on curls and doing one set of bench presses is unlikely to yield great upper body strength gains unless you have a specific need for biceps isolation.

Settling yourself for a very long term approach to perfecting form under load on the basic powerlifts would be time well spent. I had to relearn the lifts and as my bodyweight increased and some muscles developed there was a need for adjustments. Becoming a zen master of the lift you are worse at would be a great use of your gym time as it would involve repeated effort at a moderate to heavy load.

One of the things I love about powerlifting and also find frustrating is the certainty of the weight. Lifting in a competition with unusual equipment some nerves and strict rules might make you perform slightly below your best but everybody should know that they are very unlikely to be able to lift 50kg above where their gym lifts suggest.

I am constantly frustrated that I cannot lift what I want to “that’s a bench press weight” I say to myself as I prepare to squat, but the reality is that the weight is in fact my squat weight and it’s slightly more than I did last week. I will not be able to lift a PR deadlift when my training has shown me that I’m about 30-40 kilos off where I once was. This morning’s session saw an improvement from last week and that’s all that matters – it doesn’t have to be weekly but there’s little point in training unless there’s a bit of slow upward progress.

If you’ve been around gyms for any length of time then you will know that “one “ lifter who week after week attempts the same single rep max and invariably fails. Strength is most often built around repetitions and/or multiple sets. Building strength doesn’t need to be an increase in weight on the bar week on week. Going from 5×5 to 6×5 is an increase, reducing the rest time between sets is an increase and moving the bar quicker is also an increase – most trainees would benefit from seeking out these improvements.

It’s a cliché that one should enjoy the journey but it is has more resonance when that ride was nearly cut short. Relish in your time in the gym, master the lifts you suck at and show life that you mean business.

Author – Phil Malin

Bio –

As I dive into my third decade of largely uneventful loosely organised weight training, I find myself still searching. Searching for a way to increase the weight on the bar, searching for better form, searching for more muscle and searching for greater bar speed.

When I look at my journey I am not entirely convinced that it would make a compelling movie, nor would Hollywood’s A list be seeking to play the role of a bald, overweight white guy in his mid-forties but there are many things that I have learned.

I have lived a life not without stresses, a shift working policeman for over 20 years ending up as a custody Sergeant in North London, now I run my own business, which brings its own demands. I have three kids and over a dozen pets.

Last year I spent four months laying in a hospital bed with pancreatitis, which I was proud to see made it into the top 12 most painful illness according to the NHS. I had lots of complications, infections and operations during my stay and my wife was told I “might” die at least twice and was told to “come now” to see me when I was bleeding relentlessly at the end of my “recovery”

I returned to training almost exactly one year prior to writing this article and I can honestly say that one of the things I longed for in my hospital bed, overlooking the London Eye and St Paul’s Cathedral, was the feeling of a bar in my hands, that and bourbon biscuits.

When I got that bar in my hands it appeared that someone had increased the 20kg bar dramatically, it seems complete inactivity, being nasally fed liquid nutrients, having a transgastric plastic tube coming out of my stomach and losing over 30 kilos in bodyweight is not great for one’s strength.

My journey from weakling to mediocrity continues.